Oil hurdle remains on path to Kurdish independence

July 13, 2015

From Media

Three recent developments across the Kurdish territories move the Kurds closer to political independence and economic autonomy. But despite these victories, the financial viability required by a Kurdish state or states is still in question.

In last month’s Turkish elections, the Kurdish party secured a potentially king-making bloc in parliament. In Syria, Kurdish forces, the YPG, made dramatic gains at the expense of ISIL, capturing a key border post and advancing towards the group’s capital of Raqqa. And the Kurdish region of Iraq appears to have abandoned its revenue-sharing deal with Baghdad and is again attempting to sell oil independently.

In Syria, the Kurdish cantons of Jazira and Kobani are now linked, and divided from a third region, Afrin, only by a stretch under the control of ISIL and some mixed opposition groups, from the west bank of the Euphrates to the outskirts of Aleppo. Beyond Aleppo, an uneasy anti-Assad alliance holds Idlib province and runs almost to the Mediterranean.

The Syrian Kurds are currently producing small amounts of oil for local use, from fields formerly operated by China’s Sinopec. The Sinopec fields yielded about 13,000 barrels per day in 2010, the last pre-war year, while the state Syrian Petroleum Company’s fields pumped about 200,000 bpd. But with the pipeline running through ISIL territory and on to the regime-held Homs, the Syrian Kurds cannot export their oil.

Meanwhile the Iraqi Kurds are tightening their grip on oil around Kirkuk. Their agreement to export “federal” Iraqi oil through their territory to Turkey, in return for a share of central government revenue, appears to have broken down, perhaps this time irretrievably.

The Kurds could export about 300,000 bpd from their own fields and another 300,000 bpd or more from the Kirkuk area claimed by Baghdad.

At current prices, this would generate some US$900 million per month, close to the $1 billion the Iraqi Kurdish region requires for its monthly budget.

But Baghdad is likely to resume legal opposition, making buyers wary, while the Turks will not give the Iraqi Kurds a blank cheque, particularly while the situation of the Turkish Kurds remains uncertain.

The YPG’s advances open the tantalising possibility of oil shipments from the Kurdish regions of Syria and Iraq to the Mediterranean.

But the main Syrian ports of Latakia, Baniyas and Tartus remain firmly in the Assad regime’s hands. Small quantities of Kurdish oil could be trucked to markets within Syria or smuggled through it to Turkey.

Such exports would be prone to robbery and ISIL “taxation”. Syrian Kurdish oil is heavy and poor quality, yielding little value unless processed in a sophisticated refinery.

Even if the Syrian Kurds and allied opposition secured contiguous territory to the Mediterranean, there is obviously no chance of building a pipeline under the current situation. Oil that does reach external markets would still be tainted by doubts over its legitimacy.

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has even floated the idea of a military intervention in northern Syria, with the unstated aim of preventing a united Kurdish belt.

The Iraqi and Syrian Kurds are not united either, although they have each lent the other military support against ISIL. They face tribal and party divisions. The Iraqi Kurds have a good working relationship with Turkey’s government, while the Syrian Kurds’ PYD party is closely linked to the PKK, which Ankara considers a terrorist group. They are also allied with the PUK, rivals to the KDP that dominates the Iraqi Kurdish government.

So these territorial advances do not secure the reliable, legitimate, large-scale oil exports that the landlocked Kurdish regions require to backstop a push for independence. But they do win the Kurds powerful friends abroad, most notably in Washington. And they contribute to a growing sense of the inevitability of some kind of Kurdish independence.

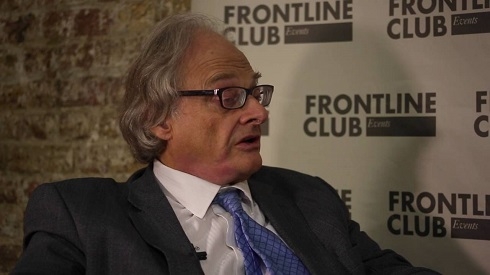

Robin Mills is the head of consulting at Manaar Energy and the author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis.