MARIANNA CHAROUNTAKI TO GULAN: PRESIDENT OF KURDISTAN REGION'S VISION "THE ONLY SENSIBLE APPROACH" FOR TROUBLED TIMES IN THE REGION

Marianna Charountaki, Senior Lecturer in International Politics at the University of Lincoln to Gulan: The vision of the President of Kurdistan Region appears to be the only sensible approach that could be adopted in these difficult times for the region.

Marianna Charountaki is Senior Lecturer in International Politics at the University of Lincoln (School of Social and Political Sciences). She has acted as Director of the Kurdistan International Studies Unit (2016-2019) at the University of Leicester. She is a BRISMES and BISA trustee and co-convener of the BISA Foreign Policy Working Group. She is also Research Fellow at Soran University (Erbil, Iraq). She has worked as consultant at the Iraqi Embassy in Athens (Greece, 2011-2012). Marianna has been researching the Middle Eastern region, in light of IR discipline, but also through extensive field work research (2007 to present). Her research lies at the intersection of IR theories, foreign policy analysis and area studies with an emphasis on the interplay between state and non-state entities as well as the latter’s conceptualisation and foreign policy standing. She is the author of the monographs The Kurds and US Foreign Policy: International Relations in the Middle East since 1945, (Routledge, 2011) and Iran and Turkey: International and Regional Engagement in the Middle East (I.B. Tauris, 2018) and co-author of Mapping Non-State Actors in International Relations (Springer, 2022). She has published articles in Harvard International Review, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, International Politics Journal, Third World Quarterly, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies and others. In a written interview she answered our questions as the following.

Gulan: Obviously Iraq is struggling with enormous turmoil and daunting challenges, and as we have seen in the past this country has frequently teetered on the brink of collapse, to what extent initiatives such as Mr. Barzani's one is urgently needed to turn the situation around?

Marianna Charountaki: Iraq’s political status today is at critical moment that could be compared to the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq war. This is not only related – as it was then – to the fact that each political faction is required to find and play its role exactly 20 years later. But also, to the changing pattern of relations on regional and international levels, which make the restoration of internal order an imperative if Iraq, as one of the two key state actors in the heart of the Middle East, that aspires to pursue a dominant and independent role in the region. Having said that, the establishment of domestic order appears to be a priority, and an opportunity cannot be squandered in pursuit of outdated policies and prolonging differences. The first attempts towards collective participation and inclusive representation were made in the 2005 Iraqi Constitution. However, exclusion and non-implementation still hamper developments. Thus, in my view, this presidential call for a ‘new deal’ that brings together all parties across the Iraqi political spectrum indicates steps being taken towards implementation, indicative of a continuation of that precious momentum that the Iraqi constitution initiated. Still, such a vision requires a serious and consistent strategic plan divided into delineated phases and accompanied by specific and measurable actions that can be only realised with the participation of Iraqis across the country.

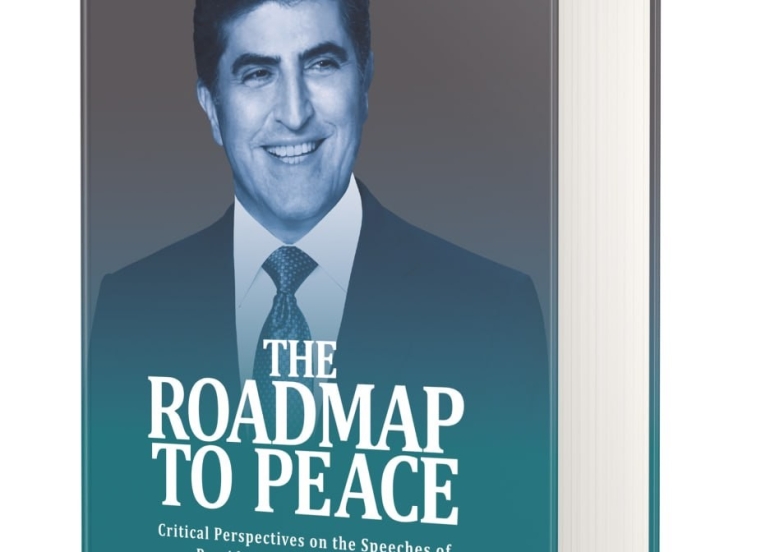

Gulan: Do you agree that this Roadmap represents pursuing a realistic, clear-sighted and far-sighted approach? and given the incredibly complicated and combustible situation of Iraq can this Roadmap be successful against all the odds?

Marianna Charountaki: Based on Iraq’s political history and developments following the 2003 war, the current status quo might look unrealistic given the successive failures to impose political order. However, on a deeper level, the vision being proposed can only be realistic and far-sighted approach in as far as the constitution and those concerned with its implementation allow. Only a resounding and widespread acceptance that the existence of a constitution that recognises and guarantees the coexistence of both Arabs and Kurds is an inalienable treasure and ultimate achievement of Iraq for Iraq can provide a foundation for long-term stability. Indeed, the importance of the constitution and its provisions are essential legacies that Iraqis should celebrate and develop. This is an extremely important task in the Middle Eastern context in light of the ongoing suffering from prolonged, unresolved issues in the region—such as with the Palestinians today—in an environment that has traditionally bred violent and belligerent approaches to conflict resolution. In this context, the vision of the President, expressed sporadically in his speeches, appears to be sufficiently realistic, and the only sensible, clear-sighted approach that could be adopted and followed in these difficult times for the region. This momentum means that the President’s initiative is of critical importance today, and perhaps the various factions of the political system are more prepared than previously to understand that the constitution itself is a far-sighted provision and possibly the only way out of the nation’s current and ongoing problems. Thus, the constitution represents the prize of the 2003 war, and the associated vision for the country a cheque written to the Iraqi people that needs to be paid. In this sense, the goal of co-existence in constitutional terms is a courageous one that can only be realised by a political personality who can build consensus and common acceptance. Iraq is undoubtedly a difficult case, but is too important to be lost in disorder and fighting, as has been the case since the 1960s—and came to a head with the war against IS.

Gulan: Do you think that this Roadmap should be part of an overarching philosophy for embarking on a major overhaul of Iraqi political system in a way that addresses the underlying root causes of the intractable problems of this country?

Marianna Charountaki:This should be the primary goal of the reformation of the Iraqi political system, including modelling of alternatives modes of governance, such as confederation. If Iraq, in the heart of the Middle East, cannot pursue structural change, given its multi-ethnic and diverse citizenship, identified by religious and spiritual nuances, any effort or vision for future progress will end up in a vicious circle of hostility. Thus, the need for a structural change must be at the forefront of leaders’ minds if the state aspires to fulfil its commitments to co-existence. The inability of the political establishment to shoulder the responsibility of not implementing a constitution that asks for separate areas of government for its population(s) under the auspices of Iraq would continue existing problems, as is clear from the results of the experiments with federal modes of governance, which have clearly reached a dead end. It is now obvious that Iraq will have to reform through a reimagining of the political system’s construction on the basis of the current constitution. Any mode of governance that ignores or is insensitive to the range of constituents within its borders—e.g. a Shi’ite majority along with a Sunni presence and a dynamic Kurdistan Region—will be doomed to the same historical failure. Such reformation does not necessarily connote the end of conflict, or signal the possibility that forces who seek to incite strife as a means of protection will vanish. However, the powers of those on the radical peripheries will be limited precisely because of the protection and equality of all those actors within the fray of governance. Constitutionally mandated co-existence within a framework of equal opportunities and obligations will increase pressure on the political establishment and related sectors to act with maturity and share responsibility for successes and failures in the eyes of international and domestic communities who value accountability.

Gulan: You have written a Book about the Kurds and the US foreign policy, and as you know US is heavily involved in Iraq in terms of diplomacy, military and economy-, to what extent US will be willing and able to play a positive role in this regard-for this Roadmap to be successful and sustainable?

Marianna Charountaki: This is a particularly interesting question that perhaps carries even greater importance today given how regional politics are currently evolving. The role of American foreign policy in the referendum, as well as US efforts to support successive governments in the “post-Maliki” era (acknowledging both the fact that premierships in Iraq are a traditional sphere of influence and the geostrategic potential of the nation) demonstrate the centrality of Iraq to successive administrations’ foreign policy. This is evidenced, in part, by the American bases in the north, and the opening of one of the largest—or perhaps the largest— American buildings in in the Middle East, situated in the Kurdistan Region. So, the question for the region now is less one of whether American foreign policy can or intends to support the federal government—and therefore solve any existing or emerging issues in Iraq—since this would have already been achieved. Rather, it seems that the problem is bigger, and stems from the inability of American foreign policy to control the (regional) powers that were raised in part by its tolerance, exacerbated in the post-Obama era by a commitment to remain steadfast in this practice. Indeed, Obama significantly altered the trajectory of American foreign policy during his first term of his office, despite the apparently consistent approach: the voids that were created either by strategy or by miscalculation remain, and require attention in the formulation of today’s US foreign policy. For this reason, the issue is not what America will do in Iraq, which has been faltering in an attempt to stabilise its goals and projects. Going back to the original question and the meaning of this book, the question is, instead, what the Iraqis will do for Iraq. So, instead of questioning attempts coming from outside, it appears to be more productive to focus on domestic initiatives and their implementation, including furthering constitutionally prescribed co-existence strategies. Indeed, both locally and internationally, the politics of questioning regional territorial integrity anew is evident. Therefore, safeguarding Iraq through the constitution, and by recognising the responsibility of all political factions to achieve its outcomes are essential if Iraq is to find its place within today’s geopolitical realities.